The Lost Museum Archive

Letters to Phil: Memories of a New York Boyhood, 1848-1856

Before they were replaced in 1865 by a paid professional force, New York City had relied completely upon volunteer fire companies, organized by neighborhoods and staffed predominantly by the working classes. The companies served a much more important social purpose than simply fighting fires; they provided a social network among the working classes, and served to foster community and neighborhood pride as competing companies raced (or fought) each other to be the first to reach a fire. The recollection of "Now one for the Big Tree!" highlights the extent to which the fire companies and their pride in the communities they served were intertwined. This nostalgic letter, written in 1887 by Gene Schermerhorn to his nephew Phil, recalls with fondness the excitement and camaraderie of "running with the masheen" in the 1840s and 50s, the hey-day of the volunteer fire companies in New York.

February 20, 1887

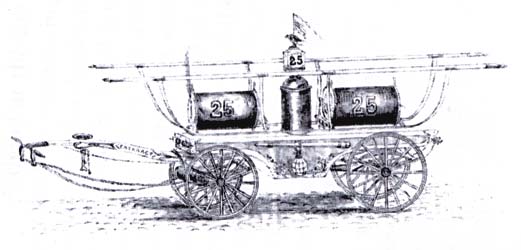

It is now time for me to tell you about something that was beginning to be of the greatest interest to me. I mean the Fires, and the Firemen, and "running with the masheen." I believe that the boys of New York have always been crazy on this subject, if I may judge from what I have heard, of the times when my uncles were boys. My uncle Phil was living with us and he had been a Fireman when he was a young man. The Fire Department was a volunteer one: that is, the men served without pay. Some of the companies were composed of most respectable men; the majority were mechanics and some were of a pretty rough class. The engine I have drawn for you was the one nearest to our house, and of course the one with which all the boys in the neighborhood "ran." "she lay" on Broadway, between 26th and 27th Streets. On the opposite side of Broadway was a famous tree—the last of its race, an immense buttonball or sycamore: one of the ornaments of the old Varian farm, which comprised all the land in this vicinity once—but this was some years before I can remember.

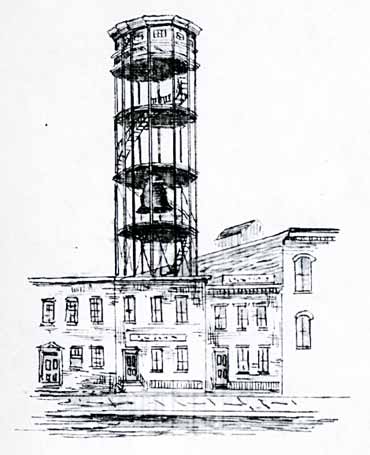

Often at a fire when the men were tired and were working slowly, someone would shout "Now one for the Big Tree" and then they would "shake her up with a will." Every company had its allotted districts to which it proceeded when an alarm was given. This was done by men who occupied Bell towers in various parts of the city: sometimes built of iron, like the one in Macdougal Street; and sometimes of wood like this one.

When these men say a fire, they struck an alarm on immense bells which could be heard a long distance. I have often head the City Hall bell in our house in 26th Street. We could recognize the different bells and always listened and counted the strokes. . .

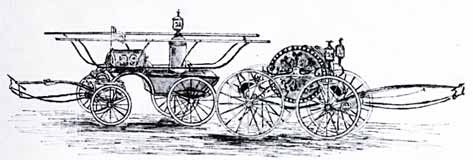

When I was down town at a later day, I sometimes ran with Southwark Engine No. 38. This was a huge "double-decker," the largest and heaviest engine in the Department. She was so heavy that they used a drag rope when going down hill to keep her from running over the men.

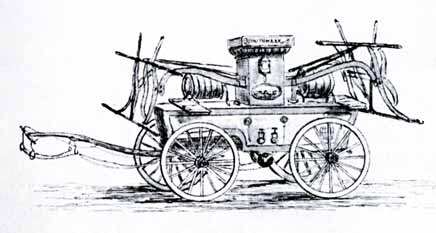

I have spoken of friendly companies. There were others that were not friends and were continually fighting. Dreadful battles were common, growing out of races and general rivalry. Sometimes there would be two or three hundred men and boys pulling an engine, and a race at such a time was very exciting, even without a fight. Of course, the boys took up these affairs in their smaller way, and fought on every occasion. It was not safe for a boy who ran with 25 to be seen near 24th Street and 8th Ave., for instance, where Mazeppa Engine No. 48 lay, or near 58th Street and Broadway, the home of Black Joke Engine No. 33: the latter in particular, having the reputation of being great fighters.

When the belles began to strike for a fire it was a strange sight: every man or boy interested, would stop short in whatever he was doing and listen, if he heard his district—and one round of the bells was enough, the streets were instantly alive with running men and boys. The first to arrive at the engine house would dash in, and seizing the tongue would yell "Fire in the 4th," of "Jefferson Market's hitting two." To be at the "tongue" was a post of honor and the Fireman, or sometimes the runner who had it was entitled to hold the "pipe" at the fire—a post of danger as well as honor. The engine was immediately run out and sometimes with just men enough to move her, but gradually numbers were added and the call was constantly for more rope until there was a crowd and we seemed to fairly fly.

Arriving at the fire, a hydrant was sought, and the hose was attached and led to the fire: the brakes were then let down, and soon the Firemen's voice would be heard from the burning building. Shouting, "Start your water, Twenty-five." Then with a yell the men would begin to "break her down" and this would go on with relays of willing arms at the breaks until the fire was out, when the Foreman would call "Vast Twenty-five" and then a few minutes later "Take up" and "Man your ropes" and we would return home.

Oh! It was vastly exciting and had a wonderful attraction for me. Day or night I was always listening for the fire bells. They would always wake me from the soundest sleep. My clothes were all laid in readiness to be occupied with as little delay as possible, and I could get out of the house in less time than you could imagine. But of course this was not till I was old enough to be out at night. Now I have written a long letter but have not told all I had to tell by any means. I have not said anything about some fires that I can remember or about the great Torchlight Parades but must leave all that for another letter.

This is the typical Fire Laddie of the East Side, Mose the Bowery Boy.

Source: Letters to Phil, Memories of a New York Boyhood, 1848-1856 by Gene Schermerhorn with thirty-four drawings by the author; foreword by Brendon Gill. New York: New York Bound; Distributed by Kampmann, 1982.