The Sectional Crisis ExhibitThe Lost Museum Archive

By the conclusion of the Mexican-American War, in 1848, military conquest had added 1.2 million square miles of new territory to the United States, and the discovery of gold in California that same year further whetted American enthusiasm for westward migration. Yet the seemingly limitless promise of expansion bore the heavy cost of a long-postponed reckoning with the question of slavery. Southern slaveholders envisioned the region as the salvation of plantation agriculture, by which overworked areas of the Southeast could be abandoned for fresh lands to the West. For Northerners, the West offered a different kind of safety valve, one that would alleviate economic pressures caused by severe economic shifts, heightened class divisions, and massive immigration from northern and western Europe. The contest over free or slave labor in the West was in fact a contest over the future of the nation.

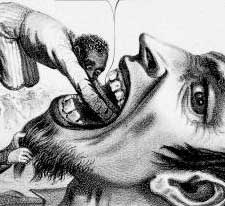

The decade began with the U.S. Congress’s Compromise of 1850, which quickly unraveled. Throughout the 1850s, escalating violence—as far away as Kansas and as nearby as the floor of the U.S. Senate—convinced many Americans that no compromise could ever resolve the conflict over slavery. Existing political parties splintered, and new parties were formed amid a body politic roiled by racism, nativism, abolitionism, and class tension. Preoccupying the nation, the political and social crises of the 1850s were reflected in several of the American Museum’s exhibits. Barnum himself underwent a political transformation during this decade, as his horror at the violence in the Kansas territories hastened his move away from the Democrats and toward the newly forged Republican Party. By 1860, Barnum was an ardent supporter of candidate and then President Abraham Lincoln